Adventist Review

24 December 1998

(Reprinted with the permission of the Adventist Review)

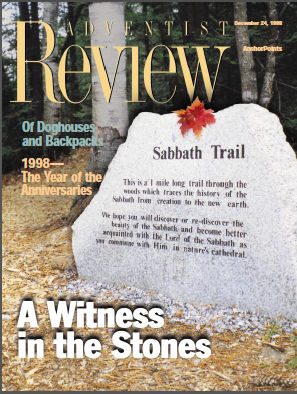

A Witness in the Stones

Updating the Sabbath afternoon walk

BY BILL KNOTT

See PDF copy for all the photos

"When your children ask in time to come, 'What do those stones mean to you?' then you shall tell them that the waters of the Jordan were cut off in front of the ark of the covenant of the Lord. When it crossed over the Jordan, the waters of the Jordan were cut off. So these stones shall be to the Israelites a memorial forever" (Joshua 4:6, 7, NRSV).

IT IS THE SLOWEST MILE I HAVE WALKED IN many a year. It is not easy to travel at a holy pace among the trees, stopping for the rest of which only my spirit feels the need. No hot, pulse-pounding rhythms here; no breathless, stopwatch calculus of distance over time.

This winding, leaf-strewn Sabbath Trail whispers counter-poise and quietness, a sweet agreement with the day the Lord has made, a covenant against the hurry of the age. Few projects emerging from Adventist hands during the past decade have better matched the message and the medium than this path through the balsams, beeches, and maples of a New Hampshire woodlot.

Sculpted from the brushy acres surrounding the historic Washington Seventh-day Adventist Church, the newly opened walking trail quietly witnesses to the significance of the Bible Sabbath that was first embraced in the old church more than 150 years ago. William Farnsworth, one of the first Millerites in Washington to embrace the seventh-day Sabbath, rests beneath a headstone in the cemetery just yards from the path. But visitors must sense that his real memorial has now risen in the woods. At 31 sites scattered along the twisting trail, 40 engraved granite markers trace a story that Farnsworth knew well-the story of the seventh-day Sabbath from the creation of the earth to its ultimate re-creation.

The Sabbath Trail was dedicated in a September 12, 1998, ceremony that drew more than 600 persons to the Washington church, and fulfills a dream for a Seventh-day Adventist pastor who served the Washington congregation for five years. Merlin Knowles, now pastor of the Conway/Berlin/Harrison district farther north, was the driving force behind the Sabbath Trail and personally responsible for script-writing, site development, and coordinating volunteer labor.

"This project really began as an answer to prayer," Knowles says. "After the Washington congregation bought the 16 acres that surround the church, I began praying that God would show us how to best use this property to highlight the important events that happened here." Four years later, visitors are unanimous in their enthusiasm about the Sabbath Trail.

"What Pastor Knowles and his team have accomplished in creating the Sabbath Trail is nothing short of astounding," says a fellow pastor who has visited the site. "They've created one of the most compellingly Adventist sites anywhere in North America."

Through providential donations of both materials and labors, actual costs for the Sabbath Trail were kept to $40,000. Denominational entities contributed approximately one quarter of the needed funds, with the rest raised in small amounts from donors who believed in the project.

"It was a bit of a struggle," acknowledges Knowles, reflecting on the four years it took to bring the trail from concept to reality. "There were many days I was certain that the project would never be finished, or worse, that it was all my own hare-brained idea. I was worried that we'd never have it completed in time for the dedication service."

Even with the help of more than 500 volunteers from around the Northern New England Conference and all-day work bees involving six Seventh-day Adventist academies in Pennsylvania, New York, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine, there were still hundreds of lonely and cold hours for Knowles. The woods through which the trail winds are both rocky and swampy, and making a way across the rough ground included building one major bridge and several smaller ones, removing hundreds of boulders and stumps, and bringing in loads of fill to level the path.

"It's certainly not a piece of ground a farmer would admire," one recent visitor wrote. "This land really couldn't be used for any profitable purpose to make a living. But maybe that's a witness in its own way. The Sabbath is all about belonging, and not about usefulness. What better place to tell the story of God's day of rest than a place where the land can't be made useful, at least in the usual sense?"

"I hoped we could create an experience that affirms the beliefs of those who love the Sabbath and educates those who don't know anything about it," adds Knowles. "Letting the site and the stones speak for themselves seemed like the best way to do that. It's certainly a different kind of evangelism."

The words carved on the stones are measured, even gracious; exactly the kind of language we could wish we had used when last we told the Sabbath story to a friend of another faith or a neighbor of no particular faith. Bible references anchor each assertion, silently reminding that the Sabbath is no man-made day of worship.

Early markers link God's resting on the seventh day of Creation week to His redemptive act in freeing Israel from Egyptian slavery. Noting how God miraculously sustained His people with manna six days a week but forbade gathering it on the Sabbath, the markers illustrate God's pre-Sinai expectation that His people would hallow the day He set aside at Creation.

At the fourth stop on the trail an introductory marker gives important context. "God is love," the chiseled words begin, "and His law proceeds from this one great characteristic. Christians who are motivated by love will show love to God and love to man. In order for people to understand how love acts, God graciously gave the Ten Commandments, which further delineate the principle of love." Behind the explanation, two large, dramatic tablets crown a knoll with the complete text of the Ten Commandments, in which the fourth commandment shines in golden lettering.

Seven markers focus on Jesus' restoration of the Sabbath during His ministry on earth; an eighth reminds of Jesus' Sabbath rest in the tomb after His crucifixion, linking His roles as Creator and Redeemer. Other slabs trace wide eras when the Bible Sabbath was lost sight of or even vigorously opposed; again, the words are sensitively chosen to sum up painful centuries when faithful Sabbath keepers obeyed the fourth commandment at peril of their lives because of state- or church-sponsored persecution.

Seventh-day Adventism's debt to Sabbath keepers from other faith traditions is also gratefully acknowledged on the trail. German Ana-baptists and American Seventh Day Baptists are cited for upholding the truth about the seventh day, as is Rachel Oakes, the young Seventh Day Baptist woman who in 1844 persuaded key members of the Washington congregation to keep the Bible Sabbath.

Several markers summarize the two decades from 1844 to 1863 in which disappointed Millerites came to understand the relationship between the Bible Sabbath and the prophecies of Daniel and Revelation that under-girded their Advent hopes. But it is the Sabbath as a central Bible truth, and not as the distinguishing feature of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, that is chiefly celebrated on the stones. Walkers of whatever stripe-agnostic, Adventist, pre-Christian, Presbyterian-can find a place among the lines. No pre-recorded voices urge themselves; no tour guides offer endless interpretation. The simple weight of well-chosen words, absorbed at the pace of a stroll, lingers on the edges of the mind.

Almost equally important as the message-bearing slabs are the benches that dot the edges of the trail. The invitation to rest, so central to the biblical message of the Sabbath, finds a visual reminder in more than 30 simple wooden seats arranged to allow reflection on the words. In the retired beaver pond that backs the marker labeled "The Sabbath at the Cross," for instance, someone has nailed a rough bar horizontally on a dead snag, forming a cross from the stricken tree. It is the kind of subtlety the eye picks up only over time, as when sitting on a bench, reveling in the Sabbath rest.

These are nuances by no means lost on those of other faiths who come to walk the Sabbath Trail. "It's our favorite walk in the whole area," say two sixtyish summer residents who have lingered long past August. "We walk it all the time, and we tell everyone we know about it."

"I think that the Sabbath Trail is just about the best thing that's happened to Washington in a long time," says a Washington resident who lives two miles away. "I'm a long way from being a Seventh-day Adventist, but that trail is drawing people from all around. It's been a good thing for all of us."

The Sabbath Trail will never seem like Disneyland, nor offer entertainment for those whose vision of the Adventist past is symbolized by longish beards and gingham bonnets. Those unwilling to travel at a slower pace-a Sabbath pace-may never understand the attractions of a world in which chickadees and red squirrels are the loudest things around. But seekers and walkers-first by tens, then by hundreds, soon by thousands-will find a witness in the New Hampshire woods they cannot soon forget.

Bill Knott is an associate editor of the Adventist Review.